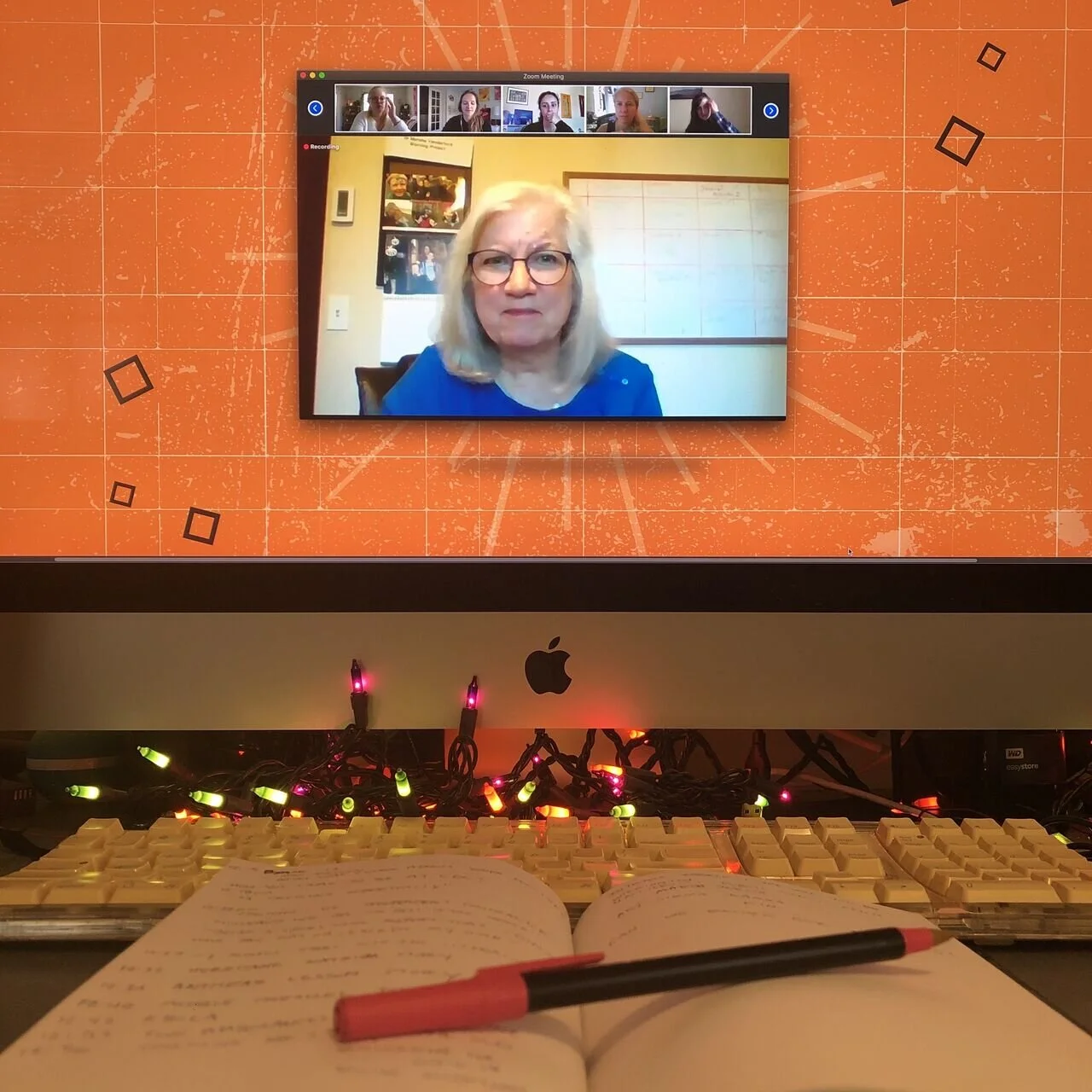

On October 30th, Orange Sparkle Ball in collaboration with Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University hosted the first of their Public Health + Webinar series about the intersection of public health and other disciplines. We were thrilled to listen as our founder, Meaghan Kennedy, sat down with Public Health communications expert Marsha Vanderford, PhD to discuss the importance of messaging in public health.

Marsha began her career like many Public Health professionals, not directly what many consider “in” Public Health. In the words of Marsha, “things just happened” to lead her to the Center for Disease and Control (CDC) and the and eventually the World Health Organization (WHO). There she led the way with transformative communication work in several historic Public Health events such as Hurricane Katrina, Anthrax attacks, and Ebola outbreak response.

Her journey with the CDC began with what she describes as a “delicious opportunity,” a fifteen minute notice, scrambling for interview attire among a suitcase packed with vacation clothes, and an adventurous nature to say “yes.” We had the opportunity to hear Marsha share some of her biggest lessons learned in Public Health messaging.

Hurricane Katrina

Marsha’s role at the CDC included leading the Emergency Communication System during Public Health emergencies such as Hurricane Katrina. The role of this unit included getting information to the general public on how to protect themselves. With several partner organizations and chains of commands, crafting a message that everyone agreed on proved to be a challenge.

Amidst the Disaster Response, the communication team developed a one-pager describing how to decontaminate drinking water with bleach. The challenge was to deliver a message that balanced practicality and accuracy. Technical experts pushed for accuracy with measures such as milliliters and droppers, while communicators pushed for practicality with the availability of these measuring tools. Ultimately, the anecdote landed in the lessons learned file, as the one-pager was never released amidst the disaster.

Marsha’s key take away from this was that “information has to be accurate but it also has to be actionable.”

Anthrax

In 2001, the deadly pathogen Anthrax, in the form of a white powder was sent to congressional and newspaper offices inside of letters.

The CDC responded by prescribing an antibiotic, ciprofloxacin, to those exposed to the letters. Soon after, experts at the CDC had determined that the process by which mail was delivered, through highly pressurized sorting systems, could have caused the pathogen to become aerosolized.

In the span of one day, Marsha coordinated a response through the Health Alert Network that prescribed postal employees who might have had contact with the letter a preventative antibiotic, doxycycline. Marsha had presented the letter to CDC experts throughout the day, who examined for accuracy and clarity. The message was approved and was urgently released that night.

The next day, Marsha awoke to her phone “ringing off the hook.”

The problem arose in the change of the antibiotics that were prescribed. Although both antibiotics had been shown to respond to Anthrax, CDC had prescribed the doxycycline to the postal employees as it was more readily available and more affordable than ciprofloxacin.

However, the change was perceived differently by the postal employees. As the White congressional employees were prescribed a more expensive medication and the postal workers, who consisted of largely African-American populations, were prescribed a cheaper alternative, the message was perceived as a form of discrimination. Ultimately, the postal employees felt that the CDC didn’t value them as much as the congressional leaders.

Through this, Marsha learned two very valuable lessons: (1) “you can lose trust in a heartbeat” and (2) amidst an emergency you must talk the public through changes and the “communication has to be clear about why” the changes are occurring.

Ebola Outbreak

While Marsha was deployed in Sierra Leone during the Ebola outbreak, the lesson learned was not uniquely hers but rather learned by the collective Public Health community. Ultimately, this lesson has shaped the future of how Public Health work is conducted.

When the WHO and other international agencies engaged in the Ebola Outbreak response they did so in the typical way, by partnering with Ministries of Health and Governments in West African countries.

Marsha described that when the WHO arrived in communities, they did so “as outsiders...with their WHO vests, and their clipboards, and their Jeeps.” While the efforts were well-intentioned, nonetheless the organizations arrived “telling people in communities...what to do and what not to do.” They aimed to deliver the sensitive message of minimizing contact with affected loved ones and of how to bury their deceased.

The fault of this approach was that communities did not trust the government in many of these countries, but rather trust was placed in local leaders within villages. Ultimately, the messages weren’t being delivered from a trusted source and the messages weren’t tailored to the communities.

As Public Health experts, we may be able to provide the technicalities of this is how the disease works and this is how we prevent it, but it must end in the “hands of the community to say this is what will work here.” Over time, what the international community learned is that community engagement is key and this has shifted into the practice and has changed how Public Health is delivered in emergencies.

Marsha’s art of storytelling left us with a broadened perspective on Messaging within Public Health. Just a few of the lessons we learned are that messages must be actionable for the audience, the audience must trust the deliverer of the message, and we must work with the community to deliver a tailored message.

To view previous and upcoming installments in the Public Health + Series click here.

Written by Liris Stephanie Berra, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Liris is a Master of Public Health student at Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University. She is part of the Global Health department, pursuing a concentration in Community Health Development and a certificate in the Social Determinants of Health.