In organizations large and small, there is often an internal drive for new initiatives to create large-scale change. Through our work at Orange Sparkle Ball…

Innovation Insights on Driving Change in Government

Columbia University data scientists help Manistee, Michigan visualize open data to see opportunity

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, the Census Open Innovation Labs (COIL) began a rural economic development sprint with university teams.

History of Public Health

Public Health + Cross-Sector Experience

A recap of our last PH+ webinar of the semester. OSB founder, Meghan Kennedy, MPH, in conversation with Niles Friedman, MPH, about the value of cross-sector experience and how to navigate career changes.

Emory REAL Experience

Public Health Innovation Analysts from Emory University’s REAL program, Liris Berra and Ryan Mathura, reflect on their experience this year at OSB.

Innovative Approaches to Pandemic Response

Public Health+ Webinar Series: Season 1

Evolve Network: Launching a Corporate Innovation Service

Thank you to Paloma Arumburu of Endeavor Perú and Lorena Molina-Irizarry of the Census Open Innovation Labs (COIL) for joining us for an Evolve Innovation Network conversation around launching a corporate innovation service.

How Do Pandemics End?

Public Health + Public Private Partnerships

On March 16th, Alexa Morse, MPH discussed public/private partnerships with Maria Thacker Goethe, MPH and Ken Berta, MBA as part of the ongoing Public Health + webinar series. Learn more from this insightful conversation.

mRNA Vaccines

Evolve Network: Launching an Innovation Program

Thank you to Lorena Molina-Irizarry of the Census Open Innovation Labs (COIL) for joining us for an Evolve Innovation Network conversation around starting an open innovation program. Lorena shared insights about lessons the COIL team has learned as they created and continue to iterate on their program. Please see below for selected insights from Lorena, as well as links to open source tools the COIL team developed.

What is COIL (Census Open Innovation Labs)

COIL explores external opportunities to solve problems identified by government groups and manages all stakeholders involved. They connect government with business and start-ups to bridge gaps and bring a wholistic view to problem solving.

Language Translation

Because different sectors use language specific to their work in the sector, one of the things Lorena stressed was a key part of the role of the COIL team is language translation. They help government groups speak to the technology teams who are working on building solutions.

Storytelling

The COIL team prioritizes storytelling, as they have found that this show and tell approach really helps people understand the value of open innovation. By effectively telling the story, you are helping audiences learn about open innovation methodologies and how well those methodologies work to create solutions to problems identified by government but working cross sector.

Community Building

Lorena noted that creating links between government and tech and also between the federal government and local communities was one of the success measures her team uses. Their goal is to seed the network effect that happens through connectivity and community building.

Tools and Examples

Lorena also provided links to the COIL open source tools, as well as examples of their work.

Resources and Toolkits:

Running Challenges and Examples:

Writing by Elle Wheelock, Evolve Innovation Analyst

Elle is an Engineering Consultant at OSB and graduated with a Physics Degree from Georgia Tech. She enjoys pushing the bounds of industry in new and exciting ways.

Emory Innovators with Meaghan Kennedy

COVID FAQs: Vaccine

COVID FAQs: Variants

We compiled some of the most common questions about the COVID-19 variants.

This article was written February 18th, 2021 and reflects the science as of that day.

Why are there variants of COVID-19?

Viruses mutate frequently. Most of the time, the mutations are harmless and have no effect on the virus at all. However, once in a while a mutation is able to amplify some characteristic. In our case, the new variants are able to spread more efficiently from person to person. As time goes on, this may become the dominant strain of the virus due to its improvement. This is evolution/natural selection/survival of the fittest happening in real time.

What are the characteristics of the variant?

The major change in the UK and South African variants is that they are more easily transmissible between people. The South African and Brazilian variants have also seemed to change the way our antibodies are able to bind to them but further research is needed to assess the differences.

Do the mRNA vaccines still work against the variant?

Early studies say yes! The vaccines are still effective against the variants however the immune response may not be as strong or prolonged.

If I’ve had COVID-19 already, should I be worried about getting the new variant still?

The reinfection possibility is still being studied, however recent research has shown that antibodies produced during infection only last up to 5 months. Even if you’ve had COVID-19 you should still take precautions to prevent infection from both variants.

Writing by Ryan Mathura, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Ryan is a Master of Public Health Student at Emory University studying Health Policy and Management. He has a background in immunology and worked in vaccine R&D before attending Emory.

Graphics by Sophie Becker, Design Strategist

Sophie is a design strategist at Orange Sparkle Ball. She is a recent graduate from RIT and holds a bachelor’s in industrial design and psychology. Her studies informed her interest in using design thinking to communicate abstract and complex ideas, particularly in public health.

Public Health + Social Justice

On February 9, Orange Sparkle Ball in collaboration with Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University hosted the fifth of their Public Health + Webinar series about the intersection of public health and other disciplines. We were thrilled to listen as our founder, Meaghan Kennedy, MPH sat down with Brooke Silverthorn, JD to discuss the importance of law and social justice in public health.

Like public health, social justice is incredibly broad and encompasses various approaches across several disciplines. However, the overarching work involves achieving equal economic, political and social rights and opportunities for all. In the public health sphere, we recognize the Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) as areas that need to be addressed in order to achieve better health outcomes and achieve social justice. Brooke also works in this space through the Health Law Partnership Legal Services Clinic at the Georgia State University College of Law.

Like many of us, her path to Public Health began in a different sector. In her early career, Brooke worked as a lawyer within the Department of Children and Families. In this role, she frequently witnessed Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES), which are a list of potentially traumatic events and aspects of a child’s environment that can undermine their sense of safety, stability, and bonding. A study conducted by the CDC and Kaiser-Permanente found that some populations are more vulnerable to experiencing ACEs because of the social and economic conditions in which they live, learn, work, and play, which are components of the SDoH.

Brooke’s passion for addressing the SDoH in vulnerable populations flourished here. She shifted her focus into policy work. In her words “looking at this issue from the individual level…. wasn't enough for me.”

“When we make those policy changes...on a systemic scale, we are also helping… the individuals.”

Brooke’s current work with the Health Law Partnership (HeLP) Legal Services Clinic involves making those larger-scale changes to improve the health and well-being of children from underserved or vulnerable communities. The HeLP Clinic is a partnership between the Atlanta Legal Aid Society, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, and the Georgia State University College of Law that provides free public health legal services that address social, economic, and environmental factors through a medical-legal partnership. Brooke gave us a great example of what a medical-legal partnership might look like:

Consider a child who has been diagnosed and prescribed medication for severe asthma. After months of taking the medication, the child continues to have recurring episodes. At this point, the pediatrician asks questions such as, “Is the child taking the medication as prescribed?” Assuming, the child is adhering to the prescription, the doctor might feel that he or she has exhausted the tools of a medical professional to address this issue. Now, here’s where the HeLP model enters.

A doctor that is trained in a medical-legal partnership might examine the child’s health with a different lens and ask questions such as, “What is going on in the child’s environment that could be causing these asthma attacks?” The doctor now can refer the child to a legal team that talks directly to the child’s family to understand other factors that impact health. Through these conversations, the legal team might discover that the family is living in a building that has mold and the landlord won’t address the issue. The legal team can then provide services that work to address these root causes.

The model that the HeLP clinic utilizes is at the crux of public health innovation. Unlike some other medical-legal partnerships, the HeLP model has a classroom component where law and medical students work side-by-side to address the SDoH. This is particularly exciting for us here at Orange Sparkle Ball as, like Brooke, we love cross-disciplinary approaches to innovate solutions for complex problems. Similar to the HeLP model, our approach frequently involves not only working within our cross-disciplinary team to foster internal innovation but also encouraging our clients to consider how knowledge from other sectors can contribute to their goals.

“The health law partnership is thinking about ways that we can stay innovative… so that we can continue to serve as a model and advise other people on the lessons we’ve learned.”

Brooke shared with us a great success story where medical and law students in the program collaborated to impact a child who had been denied social security disability income. Although the student struggled both academically and socially, they did not meet the standards set by the social security administration. One of the team members suggested looking at how many standard deviations below the norm for standardized tests the child was in in order to visually illustrate the student’s academic performance. This approach not only was successful in winning the case but demonstrated interdisciplinary collaboration, where the students collectively generated the best evidence they could for their client.

What’s really incredible about Brooke’s work with the HeLP Clinic is that she's not only making a difference systemically but she’s also directly helping individuals. By fostering collaboration between medical and law students, she contributes to a model that considers health holistically, ultimately breaking silos that exist in systems such as healthcare. As an educator, Brooke enlightens students who will be leaders in their fields and can advocate for these holistic approaches.

The notion of systemic change and interdisciplinary collaboration has been a recurrent theme across several of the Public Health + webinars. It has become apparent that in order to impact individuals, and ultimately promote systemic change it is necessary to break the silos that exist between sectors. It’s not easy to accomplish but models such as the HeLP Clinic serve as a testament that it is possible.

To view previous and upcoming installments in the Public Health + Series click here.

Written by Liris Stephanie Berra, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Liris is a Master of Public Health student at Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University. She is part of the Global Health department, pursuing a concentration in Community Health Development and a certificate in the Social Determinants of Health.

Vaccines 101

Transportation Strategies

Planes

Air travel was almost nonexistent at the beginning of the pandemic. Flights were far and few between but now the industry has adapted with safety and sanitation precautions to keep employees and travelers healthy. However, there are still risks associated with air travel.

If you do choose to travel via airplane, make sure the airline requires passengers to wear masks. It is difficult for pathogens to spread in airplanes because of how air circulates and filters in a pressurized cabin but the mask will help even more.

Make sure to distance yourself from other passengers. This can be difficult on a crowded flight but most airlines are limiting capacity of planes and keeping middle seats empty. You can also strategically book your flights to avoid contact with large crowds. Some airlines allow you to choose your seats before booking and you can gauge how many people will be on the flight. Flights on weekdays are usually less crowded than weekend flights.

Follow the same rules you’ve been sticking to since the pandemic hit. Social distance, wear a mask, and wash your hands thoroughly and often.

Trains and other forms of public transport

Public transport is probably the most difficult method of transport to navigate during the pandemic. While most transit systems are limiting capacity, it can be difficult to feel safe in small crowded spaces. Keep up to date on rules and requirements made by local transit authorities to decide if it is a good idea to use it.

If you do choose to use public transit, follow the same rules you’ve been sticking to since the pandemic hit. Social distance, wear a mask, and wash your hands thoroughly and often.

Automobiles

If you’re in a rideshare/taxi it is very important that everyone is wearing a mask and that the windows are open if they can be. Even with a plastic divider between passengers and drivers, you are not sealed off from each other in any way.

Road trips aren’t without their share of risk either. Breaks at gas stations, rest stops, and anywhere along the way carries potential exposure to COVID, especially in high case areas.

If you do choose to take a rideshare/taxi or go on a road trip, follow the same rules you’ve been sticking to since the pandemic hit. Social distance, wear a mask, and wash your hands thoroughly and often.

Even if you don’t end up traveling during the pandemic, social distance, wear a mask and wash your hands thoroughly and often.

Writing by Ryan Mathura, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Ryan is a Master of Public Health Student at Emory University studying Health Policy and Management. He has a background in immunology and worked in vaccine R&D before attending Emory.

Graphics by Sophie Becker, Design Strategist

Sophie is a design strategist at Orange Sparkle Ball. She is a recent graduate from RIT and holds a bachelor’s in industrial design and psychology. Her studies informed her interest in using design thinking to communicate abstract and complex ideas, particularly in public health.

Aerosols Pt. 2

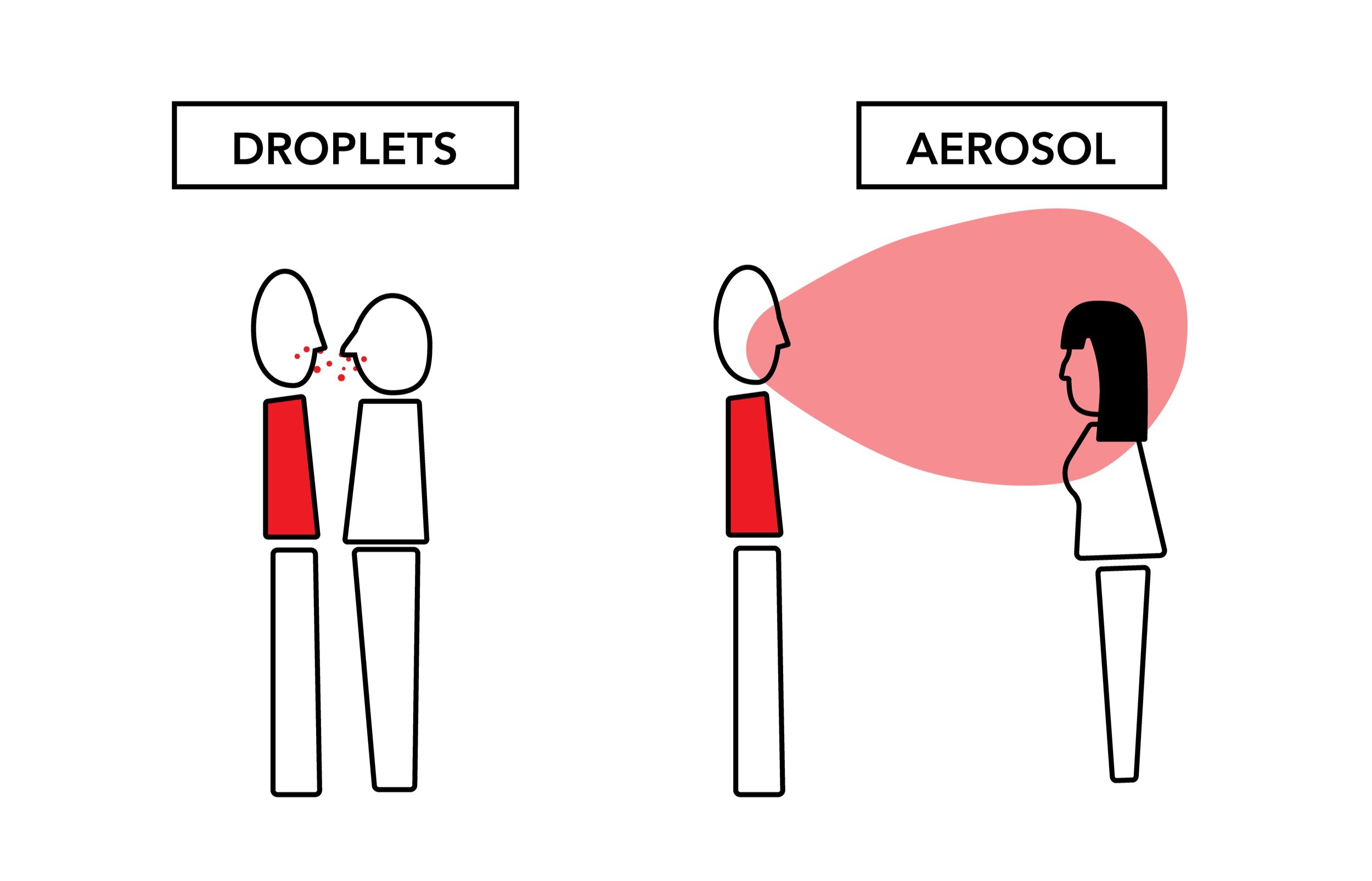

COVID-19 has proven to be an incredible infectious disease. It is able to spread in two major ways: through droplets caused by actions like coughing and then aerosols that occur while we speak and breathe. By limiting the exposure of droplets and air contaminated with the virus we can thus limit infection. Precautions such as wearing a mask, staying at least 6 feet away from other people, and limiting social gatherings to outdoor spaces all help. However, many people that gather outdoors fail to wear a mask or socially distance themselves because they think that being outdoors is enough. This is not true.

Although the risk of contracting COVID through outdoor activities is about 20 times less than indoors, the risk is still there. Modeling droplet and aerosol transmission outdoors is a lot more difficult than modeling indoor interactions due to the amount of variables to take account for. It is still important to take the proper precautions while outside to decrease the risk of transmission.

One of the most important outdoor variables that decreases transmission risk is humidity. Studies have shown that high humidity correlates to lower concentrations of aerosolized pathogens and increases the clearance of pathogens in mucus membranes (nose and throat). This leads to less risk of transmission of disease by aerosols and droplets. On the other side, low humidity increases the risk of transmission and is a main driver of cold/flu season in the late fall and winter months. While gathering outdoors, we want to have the lowest risk of transmission of COVID and other diseases. It is impossible to eliminate risk without choosing not to gather at all. To decrease the risk as much we can, it is so important to continue to socially distance and wear a mask.

Writing by Ryan Mathura, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Ryan is a Master of Public Health Student at Emory University studying Health Policy and Management. He has a background in immunology and worked in vaccine R&D before attending Emory.

Graphics by Sophie Becker, Design Strategist

Sophie is a design strategist at Orange Sparkle Ball. She is a recent graduate from RIT and holds a bachelor’s in industrial design and psychology. Her studies informed her interest in using design thinking to communicate abstract and complex ideas, particularly in public health.