In order to better understand how COVID-19 began and where it’s going, we need to take a step back and look at how pandemics happen in general.

First and foremost: What is a coronavirus? Coronaviruses are a group of viruses that can cause respiratory infections in humans ranging from mild symptoms (like the common cold) to lethal diseases (SARS, MERS, COVID-19). Mammals, including bats and humans, play host to a number of different organisms, including viruses which are known as the virome. Bats are a known natural reservoir of coronaviruses.

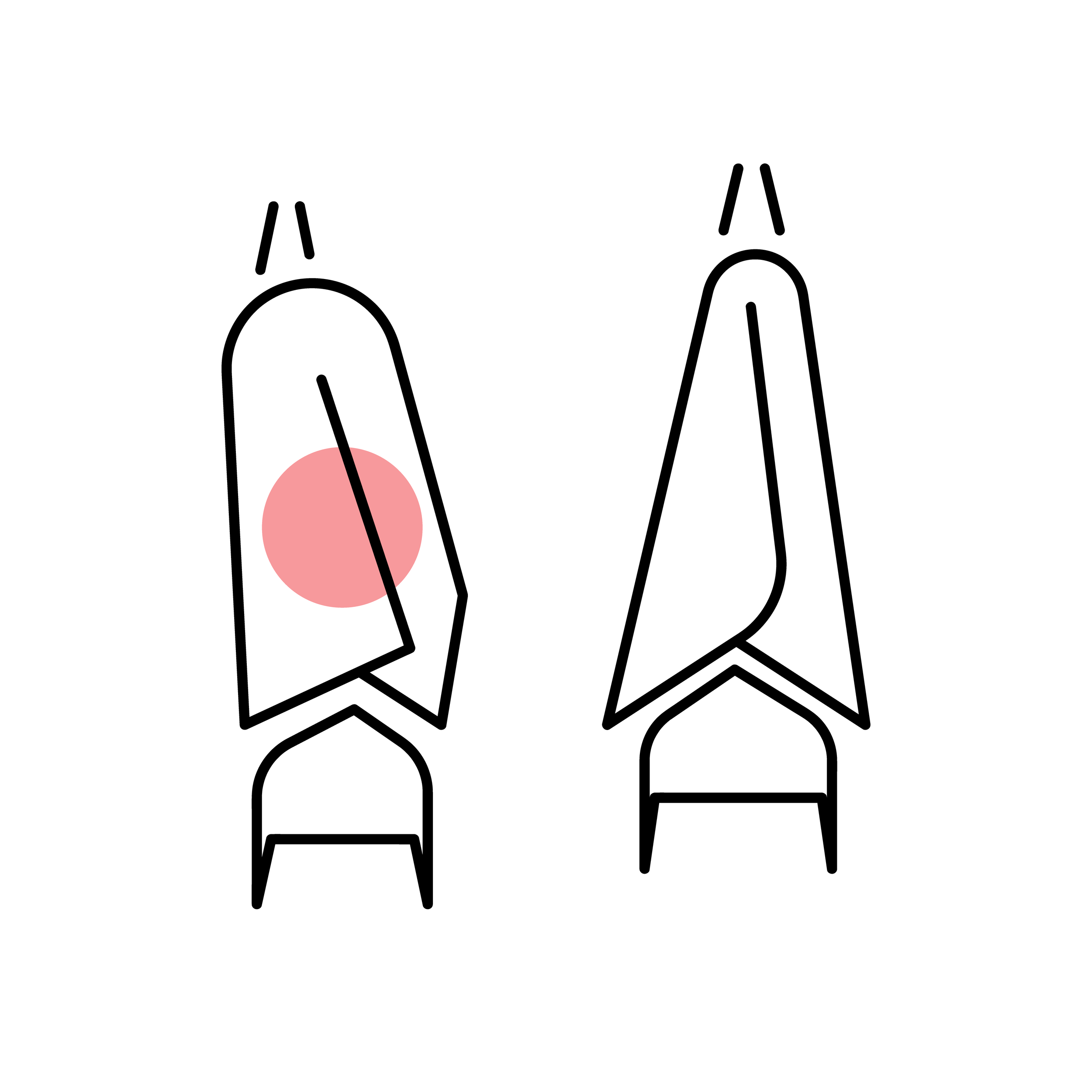

Even though many animals host a wide variety of bacteria, viruses, and fungi, they generally virtually have no effect on their health. These hosts are referred to as natural reservoirs of pathogens. For example, bats naturally carry coronaviruses and are unaffected. Bats live in cramped conditions and viruses have the opportunity to spread and mutate often between them. These often mutations are known collectively as antigenic drift. It is an important step for the virus to go from bat to bat.

Viruses in particular are very susceptible to mutations as they move from one host to another. The speed and frequency of mutations are linked to how often the pathogen is transmitted. These mutations are often harmless because they are more or less random but sometimes they develop certain attributes to make them a little more severe. Collectively, these mutations are also known as antigenic drift. In the case of COVID-19, unregulated wet markets were a source of interaction between bats in a new capacity. Cages are often stacked on top of each other and excrement from other bats or completely different animals are sources of biological material. These wet markets are also a source of interaction between bats and humans.

For the pathogen to be able to cause disease in humans, it needs to be exposed to our bodies. Many of the viruses humans are infected with today originated in livestock. Cows and horses carried the virus that became smallpox. Birds and pigs naturally carry influenza. People handling or potentially eating bats creates that necessary exposure. Bat to human mutation resulting in human infection is the next key step, also known as antigenic shift. Eventually, the virus mutates enough to be transmitted from human to human effectively.

As with most illnesses, people are able to infect others before they start feeling sick. They are able to travel and spread it to others before the onset of their own symptoms. Often people can be infected without ever showing symptoms, known as being asymptomatic. This has been a major hurdle with COVID-19, recent studies have shown that people that are infected are the most infectious 2 days before they start showing symptoms. In that time people can travel and be exposed to thousands of others.

The virus eventually becomes more serious and there are reports of higher rates of pneumonia-like illnesses at its original location and the surrounding areas. Not before long, more unusual cases are reported around the country and eventually the continent. Once the pathogen is characterized, the race is on to contain, treat, and prevent it from infecting others. This brings us to where we are today, working to stop the virus to save lives.

Writing by Ryan Mathura, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Ryan is a Master of Public Health Student at Emory University studying Health Policy and Management. He has a background in immunology and worked in vaccine R&D before attending Emory.

Graphics by Sophie Becker, Design Strategist

Sophie is a design strategist at Orange Sparkle Ball. She is a recent graduate from RIT and holds a bachelor’s in industrial design and psychology. Her studies informed her interest in using design thinking to communicate abstract and complex ideas, particularly in public health.