With COVID-19 vaccine rollouts ramping up globally and infection cases going down, there’s finally hope of life returning to “normal”. But what does it mean for a pandemic to “end”?

Public Health + Public Private Partnerships

On March 16th, Alexa Morse, MPH discussed public/private partnerships with Maria Thacker Goethe, MPH and Ken Berta, MBA as part of the ongoing Public Health + webinar series. Learn more from this insightful conversation.

mRNA Vaccines

COVID FAQs: Vaccine

COVID FAQs: Variants

We compiled some of the most common questions about the COVID-19 variants.

This article was written February 18th, 2021 and reflects the science as of that day.

Why are there variants of COVID-19?

Viruses mutate frequently. Most of the time, the mutations are harmless and have no effect on the virus at all. However, once in a while a mutation is able to amplify some characteristic. In our case, the new variants are able to spread more efficiently from person to person. As time goes on, this may become the dominant strain of the virus due to its improvement. This is evolution/natural selection/survival of the fittest happening in real time.

What are the characteristics of the variant?

The major change in the UK and South African variants is that they are more easily transmissible between people. The South African and Brazilian variants have also seemed to change the way our antibodies are able to bind to them but further research is needed to assess the differences.

Do the mRNA vaccines still work against the variant?

Early studies say yes! The vaccines are still effective against the variants however the immune response may not be as strong or prolonged.

If I’ve had COVID-19 already, should I be worried about getting the new variant still?

The reinfection possibility is still being studied, however recent research has shown that antibodies produced during infection only last up to 5 months. Even if you’ve had COVID-19 you should still take precautions to prevent infection from both variants.

Writing by Ryan Mathura, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Ryan is a Master of Public Health Student at Emory University studying Health Policy and Management. He has a background in immunology and worked in vaccine R&D before attending Emory.

Graphics by Sophie Becker, Design Strategist

Sophie is a design strategist at Orange Sparkle Ball. She is a recent graduate from RIT and holds a bachelor’s in industrial design and psychology. Her studies informed her interest in using design thinking to communicate abstract and complex ideas, particularly in public health.

Public Health + Social Justice

On February 9, Orange Sparkle Ball in collaboration with Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University hosted the fifth of their Public Health + Webinar series about the intersection of public health and other disciplines. We were thrilled to listen as our founder, Meaghan Kennedy, MPH sat down with Brooke Silverthorn, JD to discuss the importance of law and social justice in public health.

Like public health, social justice is incredibly broad and encompasses various approaches across several disciplines. However, the overarching work involves achieving equal economic, political and social rights and opportunities for all. In the public health sphere, we recognize the Social Determinants of Health (SDoH) as areas that need to be addressed in order to achieve better health outcomes and achieve social justice. Brooke also works in this space through the Health Law Partnership Legal Services Clinic at the Georgia State University College of Law.

Like many of us, her path to Public Health began in a different sector. In her early career, Brooke worked as a lawyer within the Department of Children and Families. In this role, she frequently witnessed Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES), which are a list of potentially traumatic events and aspects of a child’s environment that can undermine their sense of safety, stability, and bonding. A study conducted by the CDC and Kaiser-Permanente found that some populations are more vulnerable to experiencing ACEs because of the social and economic conditions in which they live, learn, work, and play, which are components of the SDoH.

Brooke’s passion for addressing the SDoH in vulnerable populations flourished here. She shifted her focus into policy work. In her words “looking at this issue from the individual level…. wasn't enough for me.”

“When we make those policy changes...on a systemic scale, we are also helping… the individuals.”

Brooke’s current work with the Health Law Partnership (HeLP) Legal Services Clinic involves making those larger-scale changes to improve the health and well-being of children from underserved or vulnerable communities. The HeLP Clinic is a partnership between the Atlanta Legal Aid Society, Children’s Healthcare of Atlanta, and the Georgia State University College of Law that provides free public health legal services that address social, economic, and environmental factors through a medical-legal partnership. Brooke gave us a great example of what a medical-legal partnership might look like:

Consider a child who has been diagnosed and prescribed medication for severe asthma. After months of taking the medication, the child continues to have recurring episodes. At this point, the pediatrician asks questions such as, “Is the child taking the medication as prescribed?” Assuming, the child is adhering to the prescription, the doctor might feel that he or she has exhausted the tools of a medical professional to address this issue. Now, here’s where the HeLP model enters.

A doctor that is trained in a medical-legal partnership might examine the child’s health with a different lens and ask questions such as, “What is going on in the child’s environment that could be causing these asthma attacks?” The doctor now can refer the child to a legal team that talks directly to the child’s family to understand other factors that impact health. Through these conversations, the legal team might discover that the family is living in a building that has mold and the landlord won’t address the issue. The legal team can then provide services that work to address these root causes.

The model that the HeLP clinic utilizes is at the crux of public health innovation. Unlike some other medical-legal partnerships, the HeLP model has a classroom component where law and medical students work side-by-side to address the SDoH. This is particularly exciting for us here at Orange Sparkle Ball as, like Brooke, we love cross-disciplinary approaches to innovate solutions for complex problems. Similar to the HeLP model, our approach frequently involves not only working within our cross-disciplinary team to foster internal innovation but also encouraging our clients to consider how knowledge from other sectors can contribute to their goals.

“The health law partnership is thinking about ways that we can stay innovative… so that we can continue to serve as a model and advise other people on the lessons we’ve learned.”

Brooke shared with us a great success story where medical and law students in the program collaborated to impact a child who had been denied social security disability income. Although the student struggled both academically and socially, they did not meet the standards set by the social security administration. One of the team members suggested looking at how many standard deviations below the norm for standardized tests the child was in in order to visually illustrate the student’s academic performance. This approach not only was successful in winning the case but demonstrated interdisciplinary collaboration, where the students collectively generated the best evidence they could for their client.

What’s really incredible about Brooke’s work with the HeLP Clinic is that she's not only making a difference systemically but she’s also directly helping individuals. By fostering collaboration between medical and law students, she contributes to a model that considers health holistically, ultimately breaking silos that exist in systems such as healthcare. As an educator, Brooke enlightens students who will be leaders in their fields and can advocate for these holistic approaches.

The notion of systemic change and interdisciplinary collaboration has been a recurrent theme across several of the Public Health + webinars. It has become apparent that in order to impact individuals, and ultimately promote systemic change it is necessary to break the silos that exist between sectors. It’s not easy to accomplish but models such as the HeLP Clinic serve as a testament that it is possible.

To view previous and upcoming installments in the Public Health + Series click here.

Written by Liris Stephanie Berra, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Liris is a Master of Public Health student at Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University. She is part of the Global Health department, pursuing a concentration in Community Health Development and a certificate in the Social Determinants of Health.

Vaccines 101

Transportation Strategies

Planes

Air travel was almost nonexistent at the beginning of the pandemic. Flights were far and few between but now the industry has adapted with safety and sanitation precautions to keep employees and travelers healthy. However, there are still risks associated with air travel.

If you do choose to travel via airplane, make sure the airline requires passengers to wear masks. It is difficult for pathogens to spread in airplanes because of how air circulates and filters in a pressurized cabin but the mask will help even more.

Make sure to distance yourself from other passengers. This can be difficult on a crowded flight but most airlines are limiting capacity of planes and keeping middle seats empty. You can also strategically book your flights to avoid contact with large crowds. Some airlines allow you to choose your seats before booking and you can gauge how many people will be on the flight. Flights on weekdays are usually less crowded than weekend flights.

Follow the same rules you’ve been sticking to since the pandemic hit. Social distance, wear a mask, and wash your hands thoroughly and often.

Trains and other forms of public transport

Public transport is probably the most difficult method of transport to navigate during the pandemic. While most transit systems are limiting capacity, it can be difficult to feel safe in small crowded spaces. Keep up to date on rules and requirements made by local transit authorities to decide if it is a good idea to use it.

If you do choose to use public transit, follow the same rules you’ve been sticking to since the pandemic hit. Social distance, wear a mask, and wash your hands thoroughly and often.

Automobiles

If you’re in a rideshare/taxi it is very important that everyone is wearing a mask and that the windows are open if they can be. Even with a plastic divider between passengers and drivers, you are not sealed off from each other in any way.

Road trips aren’t without their share of risk either. Breaks at gas stations, rest stops, and anywhere along the way carries potential exposure to COVID, especially in high case areas.

If you do choose to take a rideshare/taxi or go on a road trip, follow the same rules you’ve been sticking to since the pandemic hit. Social distance, wear a mask, and wash your hands thoroughly and often.

Even if you don’t end up traveling during the pandemic, social distance, wear a mask and wash your hands thoroughly and often.

Writing by Ryan Mathura, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Ryan is a Master of Public Health Student at Emory University studying Health Policy and Management. He has a background in immunology and worked in vaccine R&D before attending Emory.

Graphics by Sophie Becker, Design Strategist

Sophie is a design strategist at Orange Sparkle Ball. She is a recent graduate from RIT and holds a bachelor’s in industrial design and psychology. Her studies informed her interest in using design thinking to communicate abstract and complex ideas, particularly in public health.

Aerosols Pt. 2

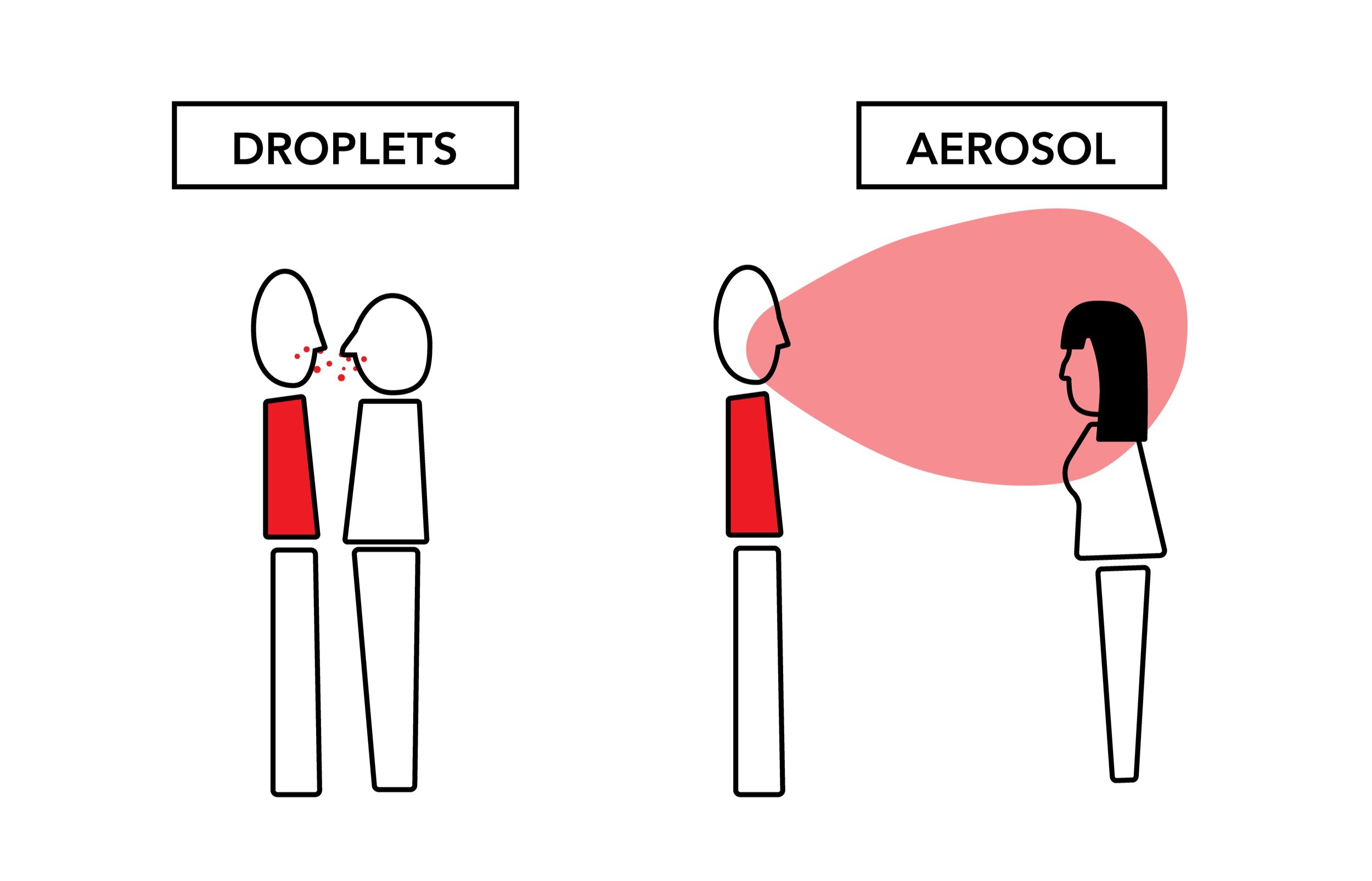

COVID-19 has proven to be an incredible infectious disease. It is able to spread in two major ways: through droplets caused by actions like coughing and then aerosols that occur while we speak and breathe. By limiting the exposure of droplets and air contaminated with the virus we can thus limit infection. Precautions such as wearing a mask, staying at least 6 feet away from other people, and limiting social gatherings to outdoor spaces all help. However, many people that gather outdoors fail to wear a mask or socially distance themselves because they think that being outdoors is enough. This is not true.

Although the risk of contracting COVID through outdoor activities is about 20 times less than indoors, the risk is still there. Modeling droplet and aerosol transmission outdoors is a lot more difficult than modeling indoor interactions due to the amount of variables to take account for. It is still important to take the proper precautions while outside to decrease the risk of transmission.

One of the most important outdoor variables that decreases transmission risk is humidity. Studies have shown that high humidity correlates to lower concentrations of aerosolized pathogens and increases the clearance of pathogens in mucus membranes (nose and throat). This leads to less risk of transmission of disease by aerosols and droplets. On the other side, low humidity increases the risk of transmission and is a main driver of cold/flu season in the late fall and winter months. While gathering outdoors, we want to have the lowest risk of transmission of COVID and other diseases. It is impossible to eliminate risk without choosing not to gather at all. To decrease the risk as much we can, it is so important to continue to socially distance and wear a mask.

Writing by Ryan Mathura, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Ryan is a Master of Public Health Student at Emory University studying Health Policy and Management. He has a background in immunology and worked in vaccine R&D before attending Emory.

Graphics by Sophie Becker, Design Strategist

Sophie is a design strategist at Orange Sparkle Ball. She is a recent graduate from RIT and holds a bachelor’s in industrial design and psychology. Her studies informed her interest in using design thinking to communicate abstract and complex ideas, particularly in public health.

Personal Strategies

We've published many different infographics over the last fews months outlining the different actions you can take to slow the spread of the virus and protect yourself and others. Here's a compilation of the key ideas:

Wear a Mask

Not all masks are created equal. If available, always try to get a K/N95 or surgical mask. Make sure to wear it properly (covering nose and mouth), dispose of or clean frequently, and still distance when wearing one.

K/N95 - The gold standard, filters 95% of SARS-COV-2. Can be disinfected after wearing for reuse.

Surgical - 2nd place, filters 95% of SARS-COV-2. Single-use only.

Cloth masks - Make sure these masks are made of safe and breathable materials. Models have shown that multiple layers of a cotton blend offer the best balance of filtration and breathability.

Face shields - Should only be used in combination with effective masks. Alone they do nothing.

Bandanas, scarves, gaiters, fleece, etc. - Not effective and some materials can actually exacerbate aerosol spread.

Learn more about masks here.

Wash Your Hands

While it’s mostly aerosol based transmission with COVID-19, you still need to take precautions with surfaces. Washing your hands with clean running water and soap can remove 99.99% of germs, including COVID-19, from your hands. Because of how easy and effective handwashing is, there is a significant investment in handwashing promotional materials demonstrating effective practices.

Get a Flu Vaccine

Getting your flu shot not only protects yourself but everyone around you. It also keeps you out of medical offices where there are other sick patients. By keeping the flu cases down, we can help ease the strain on the medical infrastructure that is being overwhelmed by COVID patients. We can keep hospital beds, medical personnel, and vital supplies open to other patients. Learn more here.

Writing by Ryan Mathura, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Ryan is a Master of Public Health Student at Emory University studying Health Policy and Management. He has a background in immunology and worked in vaccine R&D before attending Emory.

Graphics by Sophie Becker, Design Strategist

Sophie is a design strategist at Orange Sparkle Ball. She is a recent graduate from RIT and holds a bachelor’s in industrial design and psychology. Her studies informed her interest in using design thinking to communicate abstract and complex ideas, particularly in public health.

Public Health + Environmental Justice

How Pandemics Happen: Pt. 1

Masks 101

There are so many different masks available for purchase now. When the pandemic started, there was a shortage and most people just used what they could get their hands on. Homemade cloth masks were worn by most, while surgical masks and the gold standard N95 were reserved for front-line workers and essential personnel. Now that all kinds of masks are available, what are the differences between them?

N95 / KN95

These masks are rated for their ability to filter particles that are 0.3 microns in diameter. The 95 signifies that they are able to filter 95% of these particles. There are also 99 and 100 masks but they are not widely available for consumers. They are rated at filtering this size because of their intended use, non-biological safety. However due to the material they are made of, these masks are able to filter particles less than 0.1 microns in diameter (SARS-COV-2 is reported as 0.12 microns). These masks are the most effective widely produced masks and reusable. To clean them at home just spray them thoroughly with rubbing alcohol or hydrogen peroxide and let them air dry for at least 24 hours. There are also procedures where the mask is placed in an oven set on a low temperature, however this may damage the mask straps if they are attached by adhesives.

Surgical Masks

Most surgical masks that are found in stores are rated at US Level 1 meaning they filter 95% of 3.0 micron diameter particles and 95% of 0.1 micron particles. Surgical masks are rated at smaller filtration sizes because they are used in biological settings where bacteria and viruses are present. These masks are available to purchase in large packs but it is important to only use each mask once. They cannot be cleaned like N95 or cloth masks because of the type of plastic used to make them.

Cloth Masks

If N95 or surgical masks are unavailable to you, cloth masks can be used as a substitute. When searching for cloth masks, there is a balance between breathability and efficiency. If making your own, the best material for both is actually high thread count antimicrobial pillow cases. A single layer of a pillowcase offers 60% filtration against 0.02-micron particles, much smaller than the SARS-COV-2 virus. If purchasing cotton masks, look for masks that are made of multiple layers of a cotton blend. Both of these cloth masks can be washed either by hand or in a washing machine with detergent or soap and dried in a machine or in the air depending on the strap. If the straps are glued on, make sure not to expose them to too much heat.

Bandanas/Gaiters/Scarves

Not effective at air filtration for users and people around you. Certain materials, most notably fleece, actually helps create more droplets and increase the spread of pathogens in the air.

Face shields

Not effective at shielding against airborne pathogens.

Writing by Ryan Mathura, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Ryan is a Master of Public Health Student at Emory University studying Health Policy and Management. He has a background in immunology and worked in vaccine R&D before attending Emory.

Graphics by Sophie Becker, Design Strategist

Sophie is a design strategist at Orange Sparkle Ball. She is a recent graduate from RIT and holds a bachelor’s in industrial design and psychology. Her studies informed her interest in using design thinking to communicate abstract and complex ideas, particularly in public health.

COVID 101: Infographic Collection

Public Health + Community Networks

In case you missed it: A recap of the discussion between Teri Gartska, Ph.D., Associate Director of CPPR at the University of Kansas and Isabelle Swiderski, MA, MBA, Founder of Seven25 about systems thinking and how Public Health practitioners can break silos between various systems.

Get a Flu Vaccination

Why the Flu Vaccination Protects Everyone

Getting your flu vaccine is particularly important this year. Although the flu vaccine does not make you immune to COVID-19, it does significantly decrease your chances of being exposed in healthcare settings. It is important to note that the influenza virus causes the flu and SARS-COV-2 causes COVID-19. The flu shot lessens the likelihood of getting the flu which protects you from getting both the flu and COVID which would be dangerous.

With the predicted third wave of COVID-19 cases hitting the United States (and most of the world) during the late fall and early winter months of 2020, hospitals and healthcare facilities are being overwhelmed by COVID patients. As of early December in the US, there are nearly 100,000 people currently hospitalized due to severe COVID symptoms and inching towards 15 million cumulative infections.

Over the course of the 2019-2020 flu season, the CDC estimates that there were 17 million medical visits, 500 thousand hospitalizations, and 34 thousand deaths attributable to the flu in the United States. Although estimates for the 2020-2021 season so far are much lower than previous years due to social distancing measures and people wearing masks, it is important to mitigate the risk as much as possible. If more people get the vaccine, less will be seriously hospitalized with the flu which will open up hospital beds and capacity.

By getting the flu shot, you’re not only protecting yourself. You are also protecting those around you like the elderly, people who have allergies to vaccines, and arguably most importantly, medical caregivers. This will lighten hospital personnel’s workload and allow for a higher level of care capacity. The flu vaccine is typically anywhere between 40 and 60% effective most years, combined with social distancing and wearing masks this year, the burden of the flu can be significantly reduced from previous years.

Find where to get a flu vaccine near you:

Graphics by Sophie Becker, Design Strategist

Sophie is a design strategist at Orange Sparkle Ball. She is a recent graduate from RIT and holds a bachelor’s in industrial design and psychology. Her studies informed her interest in using design thinking to communicate abstract and complex ideas, particularly in public health.

Writing by Ryan Mathura, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Ryan is a Master of Public Health Student at Emory University studying Health Policy and Management. He has a background in immunology and worked in vaccine R&D before attending Emory.

Navigating the Holidays

With the holiday season quickly approaching, visiting families and friends is going to be very different due the COVID-19 pandemic. Limiting exposure to family members, especially our elders, is going to have to be kept in mind for safe visitations. Video chatting is the best option, but we have some risk mitigation ideas if your gathering must be in person. It’s our responsibility to protect each other and help end the pandemic.

Video chatting is the safest way to see family and friends because there’s no exposure! There are plenty of platforms out there. Get creative. Try learning new cooking techniques on video with friends. Include family members who aren’t normally able to make it in person. Treat it as an opportunity, not a waste.

Make sure to quarantine for at least 2 weeks before visiting people or being exposed to anyone outside of your bubble.

Get a COVID virus test before you travel and upon arrival. Be aware that a negative test doesn’t mean you’re fully safe from developing COVID or infecting others depending on when you test. Make sure to follow all testing guidelines and wear a mask to and from the facility.

Remember the basics: Wear a mask when with anyone not in your bubble (outside or inside), keep at least 6 feet of space between people, and wash your hands thoroughly and often.

The best setting for a visit is outdoors - with masks still. Try opening up the garage or adding space heaters to a patio. If you have to be indoors, take the steps to ensure proper ventilation, filtration, and humidity in indoor spaces

Graphics by Sophie Becker, Design Strategist

Sophie is a design strategist at Orange Sparkle Ball. She is a recent graduate from RIT and holds a bachelor’s in industrial design and psychology. Her studies informed her interest in using design thinking to communicate abstract and complex ideas, particularly in public health.

Writing by Ryan Mathura, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Ryan is a Master of Public Health Student at Emory University studying Health Policy and Management. He has a background in immunology and worked in vaccine R&D before attending Emory.

Public Health + Open Source Data

Orange Sparkle Ball in collaboration with Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University hosted the second event in their Public Health + Webinar series about the intersection of public health and other disciplines. This installment was particularly exciting for us here at Orange Sparkle Ball as it touched on the intersection of Public Health, Innovation, and Open Source Data.

We had the opportunity to learn from Lorena Molina-Irizarry, Director of Operations at the Census Open Innovation Labs (COIL) within the U.S. Census Bureau. Lorena's work at COIL is guided by “understanding how co-designing and creating with others... helps in pushing innovation forward.”

As the leader of The Opportunity Project, Lorena works to create a culture of Open Innovation influenced by key pillars such as citizen science, open data collaboration, and idea generation.

Within The Opportunity Project, Lorena and her team facilitate a sprint process that brings various sectors together to solve some of the nation's toughest challenges. The beauty of this project lies in the emphasis on cross-sector collaboration.

In Lorena’s words, “all stakeholders, regardless of the industry, regardless if you’re coming from a start-up, or if you’re a student in a University, or you’re an entrepreneur, big tech or big corporations, government, or community organizations... the one thing that brings us together is that everybody is trying to solve the same problems.”

The Opportunity Project aims to “solve some of the biggest challenges we face as a nation by” breaking those silos and facilitating collaboration.

Last year, The Opportunity Project focused on a problem space surrounding a prominent public health issue, the opioid crisis. One successful innovation that arose from this sprint process is a predictive analytics tool that was developed to identify the likelihood of where and when opioid emergencies would occur. By integrating Census and New York incident data, the tool allows first responders in New York to identify geographical areas where opioid emergency incidents might take place.

Prompted by demos of incredible tools such as this one, Lorena’s discussion left us with a desire to further explore some of the open source data sets that The Opportunity Project has curated.

Interested? Learn more about how to sign up for a sprint and the upcoming demo week here:

To view previous and upcoming installments in the Public Health + Series click here.

Written by Liris Stephanie Berra, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Liris is a Master of Public Health student at Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University. She is part of the Global Health department, pursuing a concentration in Community Health Development and a certificate in the Social Determinants of Health.

Public Health + Messaging

On October 30th, Orange Sparkle Ball in collaboration with Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University hosted the first of their Public Health + Webinar series about the intersection of public health and other disciplines. We were thrilled to listen as our founder, Meaghan Kennedy, sat down with Public Health communications expert Marsha Vanderford, PhD to discuss the importance of messaging in public health.

Marsha began her career like many Public Health professionals, not directly what many consider “in” Public Health. In the words of Marsha, “things just happened” to lead her to the Center for Disease and Control (CDC) and the and eventually the World Health Organization (WHO). There she led the way with transformative communication work in several historic Public Health events such as Hurricane Katrina, Anthrax attacks, and Ebola outbreak response.

Her journey with the CDC began with what she describes as a “delicious opportunity,” a fifteen minute notice, scrambling for interview attire among a suitcase packed with vacation clothes, and an adventurous nature to say “yes.” We had the opportunity to hear Marsha share some of her biggest lessons learned in Public Health messaging.

Hurricane Katrina

Marsha’s role at the CDC included leading the Emergency Communication System during Public Health emergencies such as Hurricane Katrina. The role of this unit included getting information to the general public on how to protect themselves. With several partner organizations and chains of commands, crafting a message that everyone agreed on proved to be a challenge.

Amidst the Disaster Response, the communication team developed a one-pager describing how to decontaminate drinking water with bleach. The challenge was to deliver a message that balanced practicality and accuracy. Technical experts pushed for accuracy with measures such as milliliters and droppers, while communicators pushed for practicality with the availability of these measuring tools. Ultimately, the anecdote landed in the lessons learned file, as the one-pager was never released amidst the disaster.

Marsha’s key take away from this was that “information has to be accurate but it also has to be actionable.”

Anthrax

In 2001, the deadly pathogen Anthrax, in the form of a white powder was sent to congressional and newspaper offices inside of letters.

The CDC responded by prescribing an antibiotic, ciprofloxacin, to those exposed to the letters. Soon after, experts at the CDC had determined that the process by which mail was delivered, through highly pressurized sorting systems, could have caused the pathogen to become aerosolized.

In the span of one day, Marsha coordinated a response through the Health Alert Network that prescribed postal employees who might have had contact with the letter a preventative antibiotic, doxycycline. Marsha had presented the letter to CDC experts throughout the day, who examined for accuracy and clarity. The message was approved and was urgently released that night.

The next day, Marsha awoke to her phone “ringing off the hook.”

The problem arose in the change of the antibiotics that were prescribed. Although both antibiotics had been shown to respond to Anthrax, CDC had prescribed the doxycycline to the postal employees as it was more readily available and more affordable than ciprofloxacin.

However, the change was perceived differently by the postal employees. As the White congressional employees were prescribed a more expensive medication and the postal workers, who consisted of largely African-American populations, were prescribed a cheaper alternative, the message was perceived as a form of discrimination. Ultimately, the postal employees felt that the CDC didn’t value them as much as the congressional leaders.

Through this, Marsha learned two very valuable lessons: (1) “you can lose trust in a heartbeat” and (2) amidst an emergency you must talk the public through changes and the “communication has to be clear about why” the changes are occurring.

Ebola Outbreak

While Marsha was deployed in Sierra Leone during the Ebola outbreak, the lesson learned was not uniquely hers but rather learned by the collective Public Health community. Ultimately, this lesson has shaped the future of how Public Health work is conducted.

When the WHO and other international agencies engaged in the Ebola Outbreak response they did so in the typical way, by partnering with Ministries of Health and Governments in West African countries.

Marsha described that when the WHO arrived in communities, they did so “as outsiders...with their WHO vests, and their clipboards, and their Jeeps.” While the efforts were well-intentioned, nonetheless the organizations arrived “telling people in communities...what to do and what not to do.” They aimed to deliver the sensitive message of minimizing contact with affected loved ones and of how to bury their deceased.

The fault of this approach was that communities did not trust the government in many of these countries, but rather trust was placed in local leaders within villages. Ultimately, the messages weren’t being delivered from a trusted source and the messages weren’t tailored to the communities.

As Public Health experts, we may be able to provide the technicalities of this is how the disease works and this is how we prevent it, but it must end in the “hands of the community to say this is what will work here.” Over time, what the international community learned is that community engagement is key and this has shifted into the practice and has changed how Public Health is delivered in emergencies.

Marsha’s art of storytelling left us with a broadened perspective on Messaging within Public Health. Just a few of the lessons we learned are that messages must be actionable for the audience, the audience must trust the deliverer of the message, and we must work with the community to deliver a tailored message.

To view previous and upcoming installments in the Public Health + Series click here.

Written by Liris Stephanie Berra, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Liris is a Master of Public Health student at Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University. She is part of the Global Health department, pursuing a concentration in Community Health Development and a certificate in the Social Determinants of Health.