By comparing how pandemics happen in general we are better able to understand how COVID-19 started and where it’s going.

Masks 101

There are so many different masks available for purchase now. When the pandemic started, there was a shortage and most people just used what they could get their hands on. Homemade cloth masks were worn by most, while surgical masks and the gold standard N95 were reserved for front-line workers and essential personnel. Now that all kinds of masks are available, what are the differences between them?

N95 / KN95

These masks are rated for their ability to filter particles that are 0.3 microns in diameter. The 95 signifies that they are able to filter 95% of these particles. There are also 99 and 100 masks but they are not widely available for consumers. They are rated at filtering this size because of their intended use, non-biological safety. However due to the material they are made of, these masks are able to filter particles less than 0.1 microns in diameter (SARS-COV-2 is reported as 0.12 microns). These masks are the most effective widely produced masks and reusable. To clean them at home just spray them thoroughly with rubbing alcohol or hydrogen peroxide and let them air dry for at least 24 hours. There are also procedures where the mask is placed in an oven set on a low temperature, however this may damage the mask straps if they are attached by adhesives.

Surgical Masks

Most surgical masks that are found in stores are rated at US Level 1 meaning they filter 95% of 3.0 micron diameter particles and 95% of 0.1 micron particles. Surgical masks are rated at smaller filtration sizes because they are used in biological settings where bacteria and viruses are present. These masks are available to purchase in large packs but it is important to only use each mask once. They cannot be cleaned like N95 or cloth masks because of the type of plastic used to make them.

Cloth Masks

If N95 or surgical masks are unavailable to you, cloth masks can be used as a substitute. When searching for cloth masks, there is a balance between breathability and efficiency. If making your own, the best material for both is actually high thread count antimicrobial pillow cases. A single layer of a pillowcase offers 60% filtration against 0.02-micron particles, much smaller than the SARS-COV-2 virus. If purchasing cotton masks, look for masks that are made of multiple layers of a cotton blend. Both of these cloth masks can be washed either by hand or in a washing machine with detergent or soap and dried in a machine or in the air depending on the strap. If the straps are glued on, make sure not to expose them to too much heat.

Bandanas/Gaiters/Scarves

Not effective at air filtration for users and people around you. Certain materials, most notably fleece, actually helps create more droplets and increase the spread of pathogens in the air.

Face shields

Not effective at shielding against airborne pathogens.

Writing by Ryan Mathura, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Ryan is a Master of Public Health Student at Emory University studying Health Policy and Management. He has a background in immunology and worked in vaccine R&D before attending Emory.

Graphics by Sophie Becker, Design Strategist

Sophie is a design strategist at Orange Sparkle Ball. She is a recent graduate from RIT and holds a bachelor’s in industrial design and psychology. Her studies informed her interest in using design thinking to communicate abstract and complex ideas, particularly in public health.

COVID 101: Infographic Collection

Rural Economic Development: R Story Tool for Economic Developers

Developed in collaboration with The Opportunity Project, R Story answers a key challenge that the team heard during product development: how to help small rural communities quickly and effectively integrate more data into their economic development efforts.

Public Health + Community Networks

In case you missed it: A recap of the discussion between Teri Gartska, Ph.D., Associate Director of CPPR at the University of Kansas and Isabelle Swiderski, MA, MBA, Founder of Seven25 about systems thinking and how Public Health practitioners can break silos between various systems.

Get a Flu Vaccination

Why the Flu Vaccination Protects Everyone

Getting your flu vaccine is particularly important this year. Although the flu vaccine does not make you immune to COVID-19, it does significantly decrease your chances of being exposed in healthcare settings. It is important to note that the influenza virus causes the flu and SARS-COV-2 causes COVID-19. The flu shot lessens the likelihood of getting the flu which protects you from getting both the flu and COVID which would be dangerous.

With the predicted third wave of COVID-19 cases hitting the United States (and most of the world) during the late fall and early winter months of 2020, hospitals and healthcare facilities are being overwhelmed by COVID patients. As of early December in the US, there are nearly 100,000 people currently hospitalized due to severe COVID symptoms and inching towards 15 million cumulative infections.

Over the course of the 2019-2020 flu season, the CDC estimates that there were 17 million medical visits, 500 thousand hospitalizations, and 34 thousand deaths attributable to the flu in the United States. Although estimates for the 2020-2021 season so far are much lower than previous years due to social distancing measures and people wearing masks, it is important to mitigate the risk as much as possible. If more people get the vaccine, less will be seriously hospitalized with the flu which will open up hospital beds and capacity.

By getting the flu shot, you’re not only protecting yourself. You are also protecting those around you like the elderly, people who have allergies to vaccines, and arguably most importantly, medical caregivers. This will lighten hospital personnel’s workload and allow for a higher level of care capacity. The flu vaccine is typically anywhere between 40 and 60% effective most years, combined with social distancing and wearing masks this year, the burden of the flu can be significantly reduced from previous years.

Find where to get a flu vaccine near you:

Graphics by Sophie Becker, Design Strategist

Sophie is a design strategist at Orange Sparkle Ball. She is a recent graduate from RIT and holds a bachelor’s in industrial design and psychology. Her studies informed her interest in using design thinking to communicate abstract and complex ideas, particularly in public health.

Writing by Ryan Mathura, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Ryan is a Master of Public Health Student at Emory University studying Health Policy and Management. He has a background in immunology and worked in vaccine R&D before attending Emory.

Navigating the Holidays

With the holiday season quickly approaching, visiting families and friends is going to be very different due the COVID-19 pandemic. Limiting exposure to family members, especially our elders, is going to have to be kept in mind for safe visitations. Video chatting is the best option, but we have some risk mitigation ideas if your gathering must be in person. It’s our responsibility to protect each other and help end the pandemic.

Video chatting is the safest way to see family and friends because there’s no exposure! There are plenty of platforms out there. Get creative. Try learning new cooking techniques on video with friends. Include family members who aren’t normally able to make it in person. Treat it as an opportunity, not a waste.

Make sure to quarantine for at least 2 weeks before visiting people or being exposed to anyone outside of your bubble.

Get a COVID virus test before you travel and upon arrival. Be aware that a negative test doesn’t mean you’re fully safe from developing COVID or infecting others depending on when you test. Make sure to follow all testing guidelines and wear a mask to and from the facility.

Remember the basics: Wear a mask when with anyone not in your bubble (outside or inside), keep at least 6 feet of space between people, and wash your hands thoroughly and often.

The best setting for a visit is outdoors - with masks still. Try opening up the garage or adding space heaters to a patio. If you have to be indoors, take the steps to ensure proper ventilation, filtration, and humidity in indoor spaces

Graphics by Sophie Becker, Design Strategist

Sophie is a design strategist at Orange Sparkle Ball. She is a recent graduate from RIT and holds a bachelor’s in industrial design and psychology. Her studies informed her interest in using design thinking to communicate abstract and complex ideas, particularly in public health.

Writing by Ryan Mathura, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Ryan is a Master of Public Health Student at Emory University studying Health Policy and Management. He has a background in immunology and worked in vaccine R&D before attending Emory.

Public Health + Open Source Data

Orange Sparkle Ball in collaboration with Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University hosted the second event in their Public Health + Webinar series about the intersection of public health and other disciplines. This installment was particularly exciting for us here at Orange Sparkle Ball as it touched on the intersection of Public Health, Innovation, and Open Source Data.

We had the opportunity to learn from Lorena Molina-Irizarry, Director of Operations at the Census Open Innovation Labs (COIL) within the U.S. Census Bureau. Lorena's work at COIL is guided by “understanding how co-designing and creating with others... helps in pushing innovation forward.”

As the leader of The Opportunity Project, Lorena works to create a culture of Open Innovation influenced by key pillars such as citizen science, open data collaboration, and idea generation.

Within The Opportunity Project, Lorena and her team facilitate a sprint process that brings various sectors together to solve some of the nation's toughest challenges. The beauty of this project lies in the emphasis on cross-sector collaboration.

In Lorena’s words, “all stakeholders, regardless of the industry, regardless if you’re coming from a start-up, or if you’re a student in a University, or you’re an entrepreneur, big tech or big corporations, government, or community organizations... the one thing that brings us together is that everybody is trying to solve the same problems.”

The Opportunity Project aims to “solve some of the biggest challenges we face as a nation by” breaking those silos and facilitating collaboration.

Last year, The Opportunity Project focused on a problem space surrounding a prominent public health issue, the opioid crisis. One successful innovation that arose from this sprint process is a predictive analytics tool that was developed to identify the likelihood of where and when opioid emergencies would occur. By integrating Census and New York incident data, the tool allows first responders in New York to identify geographical areas where opioid emergency incidents might take place.

Prompted by demos of incredible tools such as this one, Lorena’s discussion left us with a desire to further explore some of the open source data sets that The Opportunity Project has curated.

Interested? Learn more about how to sign up for a sprint and the upcoming demo week here:

To view previous and upcoming installments in the Public Health + Series click here.

Written by Liris Stephanie Berra, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Liris is a Master of Public Health student at Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University. She is part of the Global Health department, pursuing a concentration in Community Health Development and a certificate in the Social Determinants of Health.

Public Health + Messaging

On October 30th, Orange Sparkle Ball in collaboration with Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University hosted the first of their Public Health + Webinar series about the intersection of public health and other disciplines. We were thrilled to listen as our founder, Meaghan Kennedy, sat down with Public Health communications expert Marsha Vanderford, PhD to discuss the importance of messaging in public health.

Marsha began her career like many Public Health professionals, not directly what many consider “in” Public Health. In the words of Marsha, “things just happened” to lead her to the Center for Disease and Control (CDC) and the and eventually the World Health Organization (WHO). There she led the way with transformative communication work in several historic Public Health events such as Hurricane Katrina, Anthrax attacks, and Ebola outbreak response.

Her journey with the CDC began with what she describes as a “delicious opportunity,” a fifteen minute notice, scrambling for interview attire among a suitcase packed with vacation clothes, and an adventurous nature to say “yes.” We had the opportunity to hear Marsha share some of her biggest lessons learned in Public Health messaging.

Hurricane Katrina

Marsha’s role at the CDC included leading the Emergency Communication System during Public Health emergencies such as Hurricane Katrina. The role of this unit included getting information to the general public on how to protect themselves. With several partner organizations and chains of commands, crafting a message that everyone agreed on proved to be a challenge.

Amidst the Disaster Response, the communication team developed a one-pager describing how to decontaminate drinking water with bleach. The challenge was to deliver a message that balanced practicality and accuracy. Technical experts pushed for accuracy with measures such as milliliters and droppers, while communicators pushed for practicality with the availability of these measuring tools. Ultimately, the anecdote landed in the lessons learned file, as the one-pager was never released amidst the disaster.

Marsha’s key take away from this was that “information has to be accurate but it also has to be actionable.”

Anthrax

In 2001, the deadly pathogen Anthrax, in the form of a white powder was sent to congressional and newspaper offices inside of letters.

The CDC responded by prescribing an antibiotic, ciprofloxacin, to those exposed to the letters. Soon after, experts at the CDC had determined that the process by which mail was delivered, through highly pressurized sorting systems, could have caused the pathogen to become aerosolized.

In the span of one day, Marsha coordinated a response through the Health Alert Network that prescribed postal employees who might have had contact with the letter a preventative antibiotic, doxycycline. Marsha had presented the letter to CDC experts throughout the day, who examined for accuracy and clarity. The message was approved and was urgently released that night.

The next day, Marsha awoke to her phone “ringing off the hook.”

The problem arose in the change of the antibiotics that were prescribed. Although both antibiotics had been shown to respond to Anthrax, CDC had prescribed the doxycycline to the postal employees as it was more readily available and more affordable than ciprofloxacin.

However, the change was perceived differently by the postal employees. As the White congressional employees were prescribed a more expensive medication and the postal workers, who consisted of largely African-American populations, were prescribed a cheaper alternative, the message was perceived as a form of discrimination. Ultimately, the postal employees felt that the CDC didn’t value them as much as the congressional leaders.

Through this, Marsha learned two very valuable lessons: (1) “you can lose trust in a heartbeat” and (2) amidst an emergency you must talk the public through changes and the “communication has to be clear about why” the changes are occurring.

Ebola Outbreak

While Marsha was deployed in Sierra Leone during the Ebola outbreak, the lesson learned was not uniquely hers but rather learned by the collective Public Health community. Ultimately, this lesson has shaped the future of how Public Health work is conducted.

When the WHO and other international agencies engaged in the Ebola Outbreak response they did so in the typical way, by partnering with Ministries of Health and Governments in West African countries.

Marsha described that when the WHO arrived in communities, they did so “as outsiders...with their WHO vests, and their clipboards, and their Jeeps.” While the efforts were well-intentioned, nonetheless the organizations arrived “telling people in communities...what to do and what not to do.” They aimed to deliver the sensitive message of minimizing contact with affected loved ones and of how to bury their deceased.

The fault of this approach was that communities did not trust the government in many of these countries, but rather trust was placed in local leaders within villages. Ultimately, the messages weren’t being delivered from a trusted source and the messages weren’t tailored to the communities.

As Public Health experts, we may be able to provide the technicalities of this is how the disease works and this is how we prevent it, but it must end in the “hands of the community to say this is what will work here.” Over time, what the international community learned is that community engagement is key and this has shifted into the practice and has changed how Public Health is delivered in emergencies.

Marsha’s art of storytelling left us with a broadened perspective on Messaging within Public Health. Just a few of the lessons we learned are that messages must be actionable for the audience, the audience must trust the deliverer of the message, and we must work with the community to deliver a tailored message.

To view previous and upcoming installments in the Public Health + Series click here.

Written by Liris Stephanie Berra, Public Health Innovation Analyst

Liris is a Master of Public Health student at Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University. She is part of the Global Health department, pursuing a concentration in Community Health Development and a certificate in the Social Determinants of Health.

COVID & Ultraviolet

SARS-CoV-2 in the Air

COVID-19, Wildfires, Air, and You

Applied Public Health Research & Development

Running Short, Effective Pilots with Startups

This Testing Stuff is Confusing!

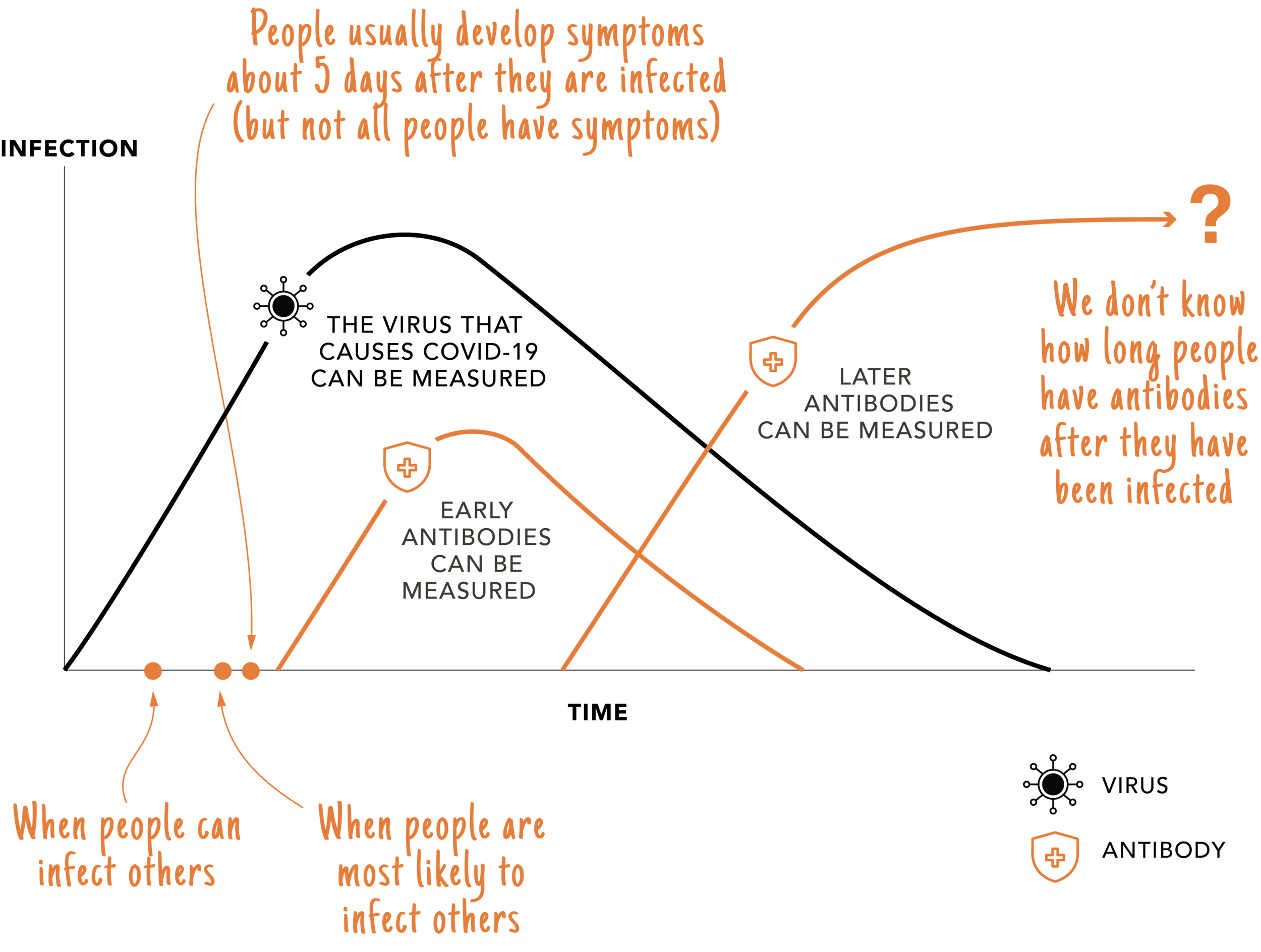

Some COVID-19 tests look for the virus (SARS-CoV-2) that causes COVID-19 and some tests measure antibodies our body creates to fight the virus. The black line below shows the virus during infection and the orange lines shows two types of antibodies that our body creates after we have been infected. This chart illustrates how SARS-CoV-2 (Virus) and antibody testing related to each other and is based on what is known as of May 2020.

How Thinking Through the Lens of Both Public Health and Business Will Allow You to Plan for the Future of Your Organization

This workshop will guide you through taking a holistic look at your organization, while also factoring in various scenarios of how the epidemic may unfold. With a more comprehensive view of the next 18 months, you can position your organization to adapt as needed, while the globe navigates this pandemic.

Tuesday, June 2, 12:00 - 1:00

Evolve Network: What Are Your External Innovation Pain Points?

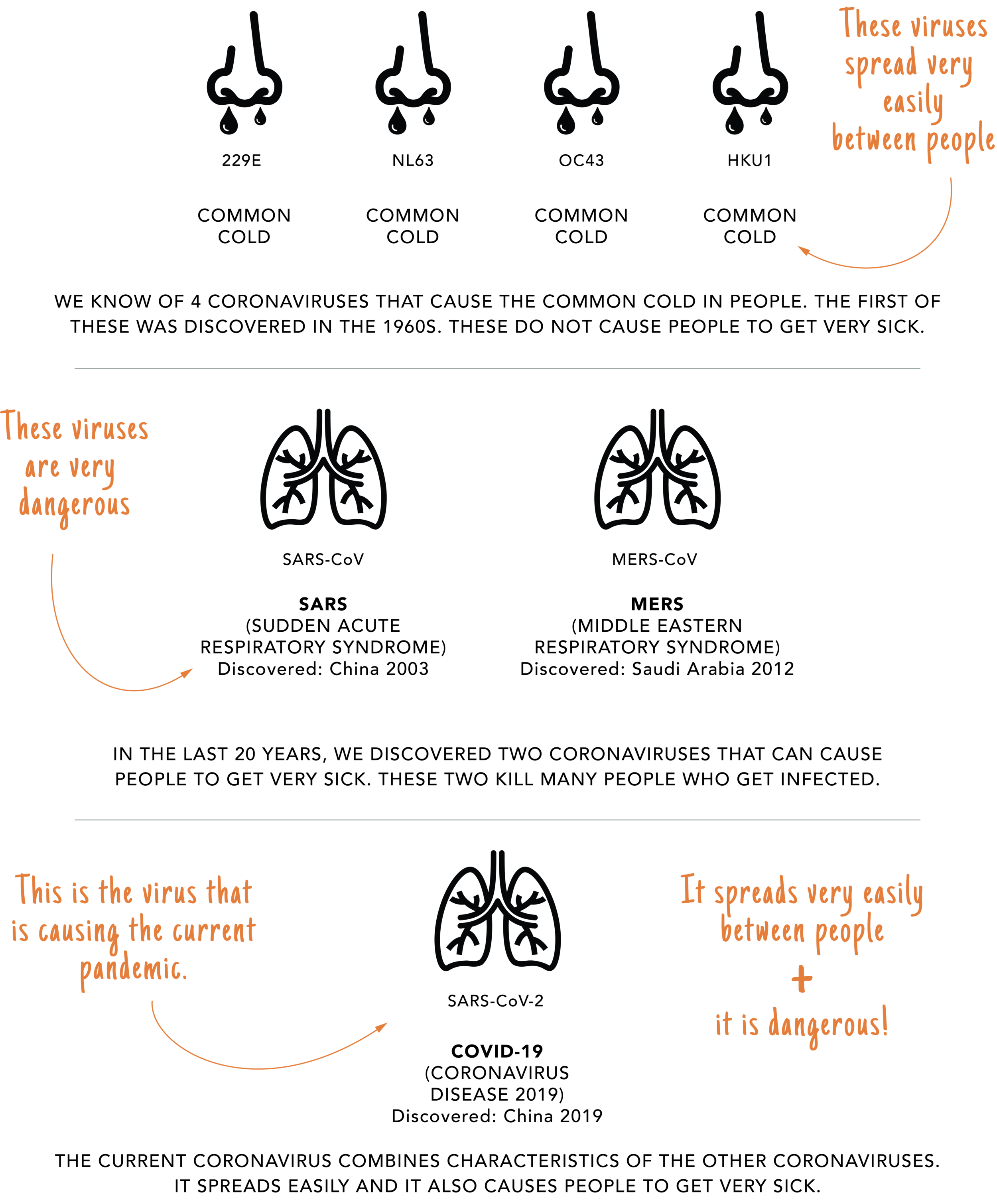

What Do We Know About Coronaviruses?

There are 7 coronaviruses that we know cause illness in people. Four of them cause upper respiratory illnesses (a.k.a., common colds). Three of them are lower respiratory illnesses and have been discovered in the last 20 years. These coronaviruses are more serious.

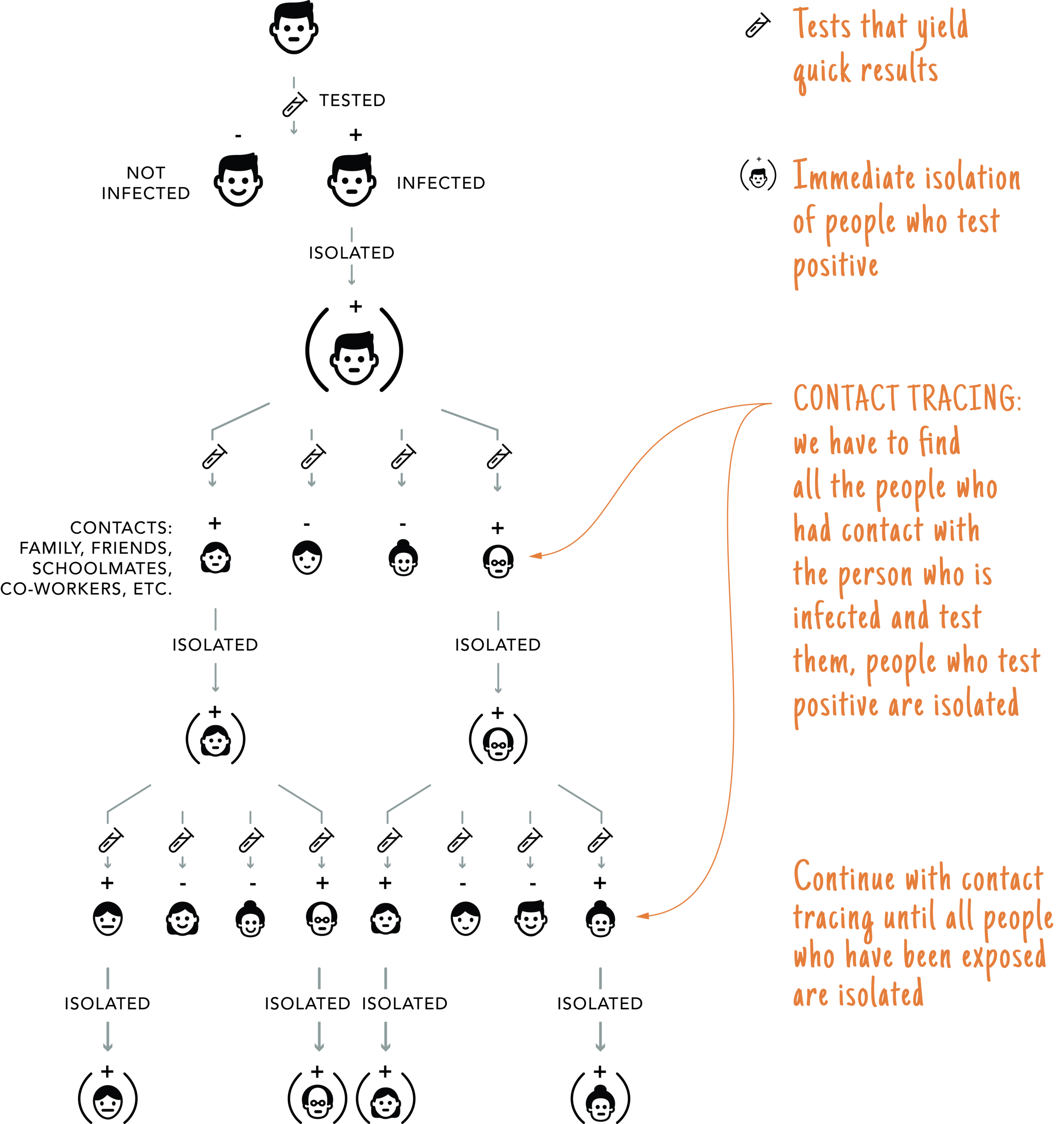

How Do We Fight an Epidemic (a.k.a. Public Health 101)?

Public Health has always been focused on epidemic prevention, using standard practices. These public health methods include testing with quick results, isolating positives and contact tracing, or looking for people who have been exposed to the infected person. These practices have been successfully used by public health practitioners through numerous epidemics.

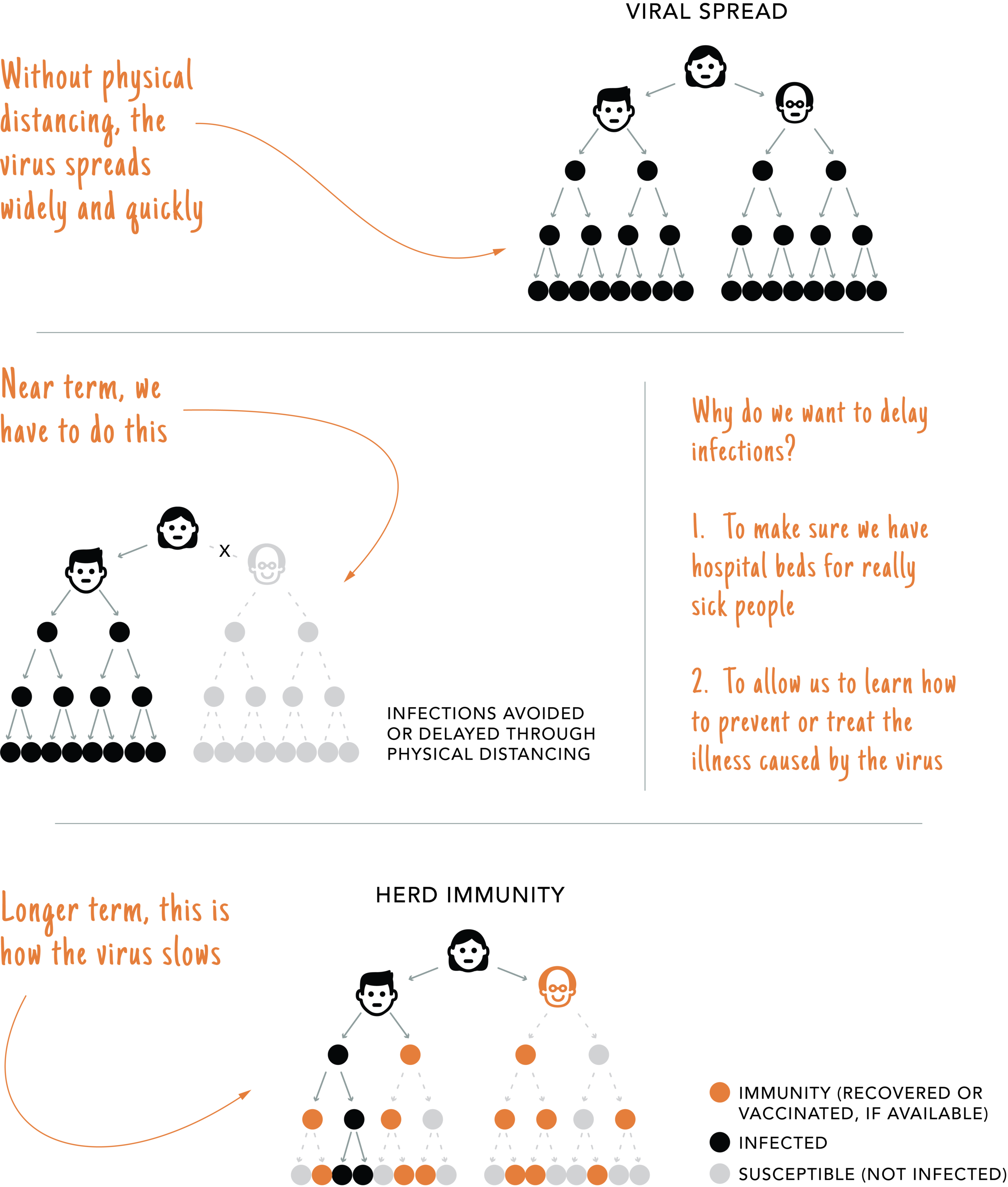

How Does a Pandemic Stop?

Physical distancing prevents infections so. we can maintain enough hospital beds and give medical professionals time to get better at treating COVID-19. Eventually, as people develop immunity or become immune because a vaccine is available, the epidemic will slow. This tipping point in immunity is called Herd Immunity and most experts think 60-70% of the population needs to be immune before the epidemic slows.